The Art of Wine Description

In the early days of wine appreciation, standard descriptions and wine as we know today did not exist. Wine was described by the gentry in high-toned literary or artistic references. One wine might strike a drinker as like a particular poem; another might be compared to star-light, a babbling brook, or an Old Master painting; the flavor profiles of others were parsed into 'masculine' and 'feminine'; the sensations produced by some wines were 'noble', one type of wine was the 'king' of drinks, another the 'queen'; one was Beethoven, another was Brahms.

For a very long time, it was understood that the sensory profiles of wines might be attended to with respect to pleasure, to physiological consequence, to aesthetics, and to their geographical identity and authenticity but without any systematic or focused attempt analytically to describe the aspects of taste or smell.

The Scientific Shift: Maynard Amerine and Objective Descriptors

Maynard A. Amerine, 1911-1998

Enter Maynard Amerine, an enologist and visionary. In the mid-20th century, Amerine and his colleagues at the University of California, Davis, embarked on a mission to transform wine evaluation. Their goal? To replace whimsical musings with objective descriptors rooted in science.

- Standardization: Amerine championed the use of standardized terminology. Instead of vague adjectives, they focused on specific attributes. “Fruity” became “notes of blackberry,” and “smooth” was dissected into “fine tannins.”

-

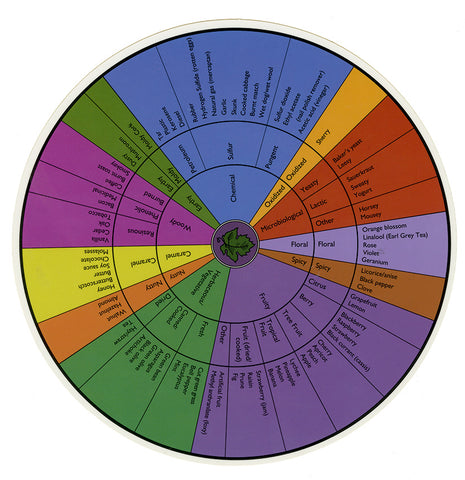

Wine Aroma Wheel: Amerine’s team developed the Wine Aroma Wheel—a visual aid that mapped out wine flavors. This wheel provided a shared vocabulary for professionals and enthusiasts alike. Suddenly, descriptors like “grassy” and “buttery” had a common meaning.

- Chemical Analysis: Amerine’s work integrated sensory science with chemistry. They identified compounds responsible for aromas and tastes. For instance, “green apple” was linked to isoamyl acetate. This bridged the gap between subjective perception and objective analysis.

Objective Descriptors Today: Bridging Tradition and Science

Fast-forward to today. Wine language has evolved, striking a balance between art and science:

- Terroir and Complexity: We still honor the terroir—the unique soil, climate, and culture of each vineyard. Subjective terms like “minerality” evoke the land’s influence. Objective analysis confirms the presence of specific minerals.

- Consumer Communication: Objective descriptors aid communication. A sommelier recommends a “crisp Sauvignon Blanc” or a “full-bodied Cabernet Sauvignon.” These terms guide consumers without overwhelming them.

- Global Market: Wine transcends borders. Objective language helps bridge cultures. A French Bordeaux described as “earthy” resonates with a New World audience.

Legacy of Scientists: A Well-Accepted Lexicon

Maynard Amerine’s legacy endures. His pursuit of objectivity transformed wine appreciation. Today, we sip wines armed with both poetic metaphors and scientific precision. The lexicon he helped create is well-accepted—a bridge between tradition and progress.

- Sensory Jumble: The concept of ‘flavor’ as a complex sensory experience, integrating taste, smell, and other sensations into a seamless whole.

- Linguistic Reform: Efforts to reform wine descriptors to be less fanciful and more objective are highlighted, aiming to facilitate reliable communication about wine’s sensory aspects.

- Analytic Vocabulary: The shift towards an analytic vocabulary for wine odors is noted, marking a move from subjective to more objective descriptions in the wine world.

- Globalization of Taste: The article touches on how the language of wine has evolved to accommodate a global market, where consumers may not have prior experience with certain wines.

So, next time you raise a glass, remember the scientists who elevated wine language from mere sentiment to a shared understanding. 🍷